I attended the first book discussion (a second one is scheduled in January) on the book The Things They Carried by Tim O’Brien this past Wednesday night. Please see my previous post about the kick off of the Big Read earlier this month. As is my wont when I attend discussions like this, I record the proceedings so I can concentrate on the lecture and discussion fully. I used to scribble notes constantly, but besides giving me a cramp, it also prevented me from participating and enjoying the experience. I contacted both Terri and Professor Prasch to gain their permission to include the recording and my transcription of the first third of the evening.

I attended the first book discussion (a second one is scheduled in January) on the book The Things They Carried by Tim O’Brien this past Wednesday night. Please see my previous post about the kick off of the Big Read earlier this month. As is my wont when I attend discussions like this, I record the proceedings so I can concentrate on the lecture and discussion fully. I used to scribble notes constantly, but besides giving me a cramp, it also prevented me from participating and enjoying the experience. I contacted both Terri and Professor Prasch to gain their permission to include the recording and my transcription of the first third of the evening.

A bit about the transcription process: Earlier in my life (say a couple of decades ago), I spent years as a legal secretary. Because I typed so fast, I inherited the most prolific attorneys in whatever office I happened to be employed at. I got to a point where I could literally type faster than most people could talk and I actually increased the speed of my transcription equipment to save time. Those days are long gone, but I still maintain a modicum of my once magical ability to race through a tape. This transcription is mostly verbatim, but I have taken the liberty to clean up some of the structure of the professor’s remarks. Professors and attorneys are very articulate when they speak, so please rest assured I only glossed over the occasional ‘um’ or ‘you know’ or ‘right? ‘ and other such phrases that all of us fall into when we are thinking and talking extemporaneously. For completeness sake, I will include the original audio files if you prefer to listen rather than peruse the transcribed content.

I plan a second sequel blog post that goes beyond Professor Prasch’s opening remarks into the discussion itself. The entire recording is over ninety minutes long and I’ve spent hours transcribing just the first 25-30 minutes. It will take my ears, my back and my fingers a day or so to recover. Please stop back by in a few days for the next installment.

Big Read Book Discussion on The Things They Carried by Tim O’Brien

November 19, 2014 ~ Lansing Community Library

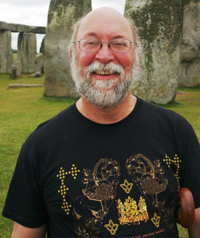

Discussion Leader: Professor Thomas Prasch,  Chair of History at Washburn University tom.prasch@washburn.edu

Chair of History at Washburn University tom.prasch@washburn.edu

Introduction by Terri Wojtalewicz, Youth Services Librarian twojo@lansing.ks.us

I wanted to thank you all for coming to our first Big Read book discussion. Today’s program is being brought to us by the Kansas Humanities Council. They are a nonprofit organization promoting the understanding of history and ideas that shaped our lives and strengthen our sense of community.

Tom Prasch is going to be our facilitator for the book discussion today. He is a professor and also chairs the History Department at Washburn University. He received his PhD in History from Indiana University and has taught on the history of the Vietnam War in his classes and has led discussions about Tim O’Brien’s inventive ways of reprocessing the war experience.

I would like to thank you so much, Tom, for coming and leading our very first book discussion here at Lansing Library.

Click here to listen to original audio recording of Terri’s introduction.

Opening Remarks by Professor Prasch:

Let me say just by way of further introduction something about the way I got into this particular topic. Obviously, teaching world history I teach the Vietnam War and the other wars in Southeast Asia, but I also have interest, even though I’m trained as a Victorian historian mostly, I have a real strong interest in film. That’s a bit of a mystery, since they didn’t have any.

But still, film and history is one of the things I’m very interested in and that’s gotten me to engage with, among other things, Oliver Stone and his sequential reworking of this experience. Stone and I have actually yelled at each other in print. But one of the things that kind of brings me to the Vietnam subject is the way that Vietnam got processed through film. And if you think about that, during the Vietnam war there were pretty much no movies about Vietnam. There were movies about other wars that were actually about Vietnam, but they were always about other wars. The most familiar example there is M*A*S*H … everyone knew it was about Vietnam but actually it’s about Korea. There were a whole bunch of movies like that in the late 60s and early 70s that used other films to talk about Vietnam. But no movies with a very few exceptions – John Wayne’s embarrassing Green Berets – very embarrassing. But with very few exceptions, no films focused on Vietnam. The first wave of films that focused on Vietnam were made by people who hadn’t been there – Deer Hunter, Apocalypse Now – and all those came out in the late 70s.

But still, film and history is one of the things I’m very interested in and that’s gotten me to engage with, among other things, Oliver Stone and his sequential reworking of this experience. Stone and I have actually yelled at each other in print. But one of the things that kind of brings me to the Vietnam subject is the way that Vietnam got processed through film. And if you think about that, during the Vietnam war there were pretty much no movies about Vietnam. There were movies about other wars that were actually about Vietnam, but they were always about other wars. The most familiar example there is M*A*S*H … everyone knew it was about Vietnam but actually it’s about Korea. There were a whole bunch of movies like that in the late 60s and early 70s that used other films to talk about Vietnam. But no movies with a very few exceptions – John Wayne’s embarrassing Green Berets – very embarrassing. But with very few exceptions, no films focused on Vietnam. The first wave of films that focused on Vietnam were made by people who hadn’t been there – Deer Hunter, Apocalypse Now – and all those came out in the late 70s.

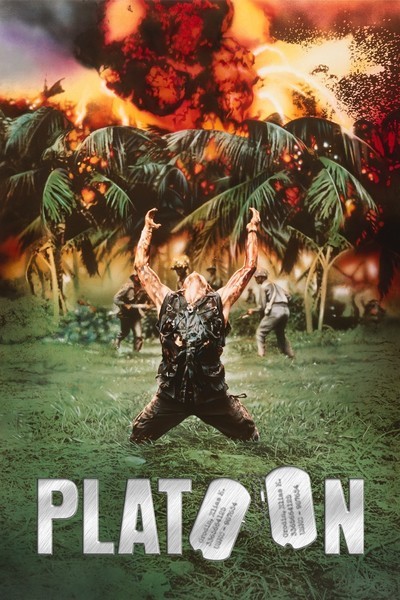

And then we get that new wave mid-80s forward, starting with Platoon, and then the whole wave of films after Platoon – Hamburger Hill and all the rest of those – that are actually done by people who had been there or had some significant role by people who had been there, with Platoon first out of the box. Stone was a veteran himself and it says something to me that for Stone it wasn’t enough to make Platoon. He ends up making three full-scale movies about the Vietnam experience: Platoon; Born on the Fourth of July; and, Heaven and Hell, which kind of tries to do it from the Vietnamese perspective. It takes three films to do that. And then if you think about Stone’s career after that, most of his significant work is still really about the Vietnam War, or the Vietnam War is a huge footnote in it. So, JFK, yes it’s about the killing of JFK but it’s also about Vietnam. And much of his later work is similar.

And then we get that new wave mid-80s forward, starting with Platoon, and then the whole wave of films after Platoon – Hamburger Hill and all the rest of those – that are actually done by people who had been there or had some significant role by people who had been there, with Platoon first out of the box. Stone was a veteran himself and it says something to me that for Stone it wasn’t enough to make Platoon. He ends up making three full-scale movies about the Vietnam experience: Platoon; Born on the Fourth of July; and, Heaven and Hell, which kind of tries to do it from the Vietnamese perspective. It takes three films to do that. And then if you think about Stone’s career after that, most of his significant work is still really about the Vietnam War, or the Vietnam War is a huge footnote in it. So, JFK, yes it’s about the killing of JFK but it’s also about Vietnam. And much of his later work is similar.

So, thinking about that and looking at literature, I think Tim O’Brien … it’s very interesting to see that he has very similar struggles representing this war and coming to terms with it. And when we get to discussion we can talk about this in, I think, two big respects. One is Vietnam as a specific set of events and the difficulties it presents for people. But a second is to what extent this is a general phenomenon. That when people come back from war… the kind of double thing of reintegrating back into society and then finding ways to think through this stuff … is always going to be a complicated process. And I think it will be really interesting, by the way, this panel discussion coming up on December 9th where you have veterans of multiple wars on the panel. I think that will be really interesting for exactly this kind of issue.

|

|

|

It happens that this semester I put together with a colleague in English a World War One course because it’s the centennial of the beginning of World War One. And I was rereading that literature again for the first time in decades. In doing so, one of the things that struck me was that all of the great works that came out of World War One came out about a decade later. Erich Marie Remarque’s All Quiet on the Western Front; Graves’ Goodbye to All That; Vera Brittain, the woman who wrote about her war experience in Testament of Youth … all those books came out in ’28, ’29. And very few things … Jünger’s Storm of Steel is the only exception … very few things came out immediately after. It took people about a decade to process and get ready to write. And I think that’s probably a pattern you find in a lot of wars.

In Vietnam there were particular problems and O’Brien is very clear on these right from the outset of this book. Unlike World War One, where at the end of it they were at least saying things like ‘the Great War’ or the ‘War to End All Wars’ which they were wrong about that but they thought that, right? Unlike World War Two which most people involved with had no qualms about in terms of the commitment to it and it’s still called the ‘Good War’ in a lot of circles. Unlike most of the conflicts in which Americans have been involved, this one by the time that O’Brien gets involved with it, is already hugely divisive. It is already something that is deeply divisive and the country feels massively different about how this war is being conducted, what we are doing there, at all levels. O’Brien himself is not a willing volunteer but a draftee. In that sense, by the way, unlike Stone who had volunteered to go, O’Brien is drafted into this war and would rather not be there. I think that’s pretty clear. Then when he comes out of it and begins to write about it, it’s going to take him three books to sort it out.

So our sense of reality gets distorted. I think he is playing with those tactics in this novel. What he does straight forwardly is a story that starts in Vietnam about – and by the way all of these books are about the Alpha Company ; they are the same guys; you can recognize figures in all three of these books; these are the guys he served with – and in this case one of them goes AWOL when they are in Cambodia when there are not supposed to be in Cambodia. And they decide that they don’t want him to get in trouble for being AWOL so they will go back and catch him and they end up in Paris. They just keep following him and following him and they end up with all their equipment, their M16s, riding the Metro, things like that, and it’s just absolutely wild but he starts from this realistic gritty depiction of war and end up in Paris with their M16s on the Metro and it’s kind of an interesting distortion of reality. And Paris isn’t entirely accidental (inaudible) but I think it’s a kind of fascinating attempt to grapple with this in straight forward novelistic terms. But that didn’t do it.

So our sense of reality gets distorted. I think he is playing with those tactics in this novel. What he does straight forwardly is a story that starts in Vietnam about – and by the way all of these books are about the Alpha Company ; they are the same guys; you can recognize figures in all three of these books; these are the guys he served with – and in this case one of them goes AWOL when they are in Cambodia when there are not supposed to be in Cambodia. And they decide that they don’t want him to get in trouble for being AWOL so they will go back and catch him and they end up in Paris. They just keep following him and following him and they end up with all their equipment, their M16s, riding the Metro, things like that, and it’s just absolutely wild but he starts from this realistic gritty depiction of war and end up in Paris with their M16s on the Metro and it’s kind of an interesting distortion of reality. And Paris isn’t entirely accidental (inaudible) but I think it’s a kind of fascinating attempt to grapple with this in straight forward novelistic terms. But that didn’t do it.

Twenty years later, he writes this. Twenty years after his service he writes this. And this book is fascinating to me because, partly because it’s fun to see what librarians do with it. They have problems filing it. And you came up with the perfect answer which is call it fiction and leave it at that. I can find you dozens of people who call this a novel. I can find you dozens of people who call it short stories. And the problem here is that it doesn’t quite work as either. As a novel, it hasn’t got your straight forward through lines and things like that that you expect a novel to have, but as a short story collection, things are too connected. It’s the same group of people in every story. Many of the stories comment on previous stories. A whole bunch of them do what neither short story collections or novels ordinarily do, which is to talk about the process of creating fiction about Vietnam. So there’s a whole lot of work here that is actually how do we do this? How do we write about Vietnam? Did I just do that story right? Let me retell it in a different way. There’s a whole bunch of that in this book.

Twenty years later, he writes this. Twenty years after his service he writes this. And this book is fascinating to me because, partly because it’s fun to see what librarians do with it. They have problems filing it. And you came up with the perfect answer which is call it fiction and leave it at that. I can find you dozens of people who call this a novel. I can find you dozens of people who call it short stories. And the problem here is that it doesn’t quite work as either. As a novel, it hasn’t got your straight forward through lines and things like that that you expect a novel to have, but as a short story collection, things are too connected. It’s the same group of people in every story. Many of the stories comment on previous stories. A whole bunch of them do what neither short story collections or novels ordinarily do, which is to talk about the process of creating fiction about Vietnam. So there’s a whole lot of work here that is actually how do we do this? How do we write about Vietnam? Did I just do that story right? Let me retell it in a different way. There’s a whole bunch of that in this book.

But at the same time, at core, any of these individual stories can be lifted out and told as a separate story. If you don’t read the next one, it holds up. If you read, the next one, it breaks down. That creates some interesting conceptual kinds of questions. I think it’s quite deliberate that he’s challenging our usual categories here. I think one thing that he kind of is saying is fundamentally Vietnam doesn’t fit normal categories. And he – of course, it’s his war – he thinks of this as something that’s utterly different from previous experience in wars. He thinks it’s fundamentally unrepresentable.

Of course, if you go back, to reading all those World War One people, most of those people thought the same thing. They thought this was the war they couldn’t possibly represent. If you think of all the really great poets who were writing about World War One during World War One, about half of them end of dying in Flanders’ Fields and places like that. You’ll notice the traditional forms are breaking down in their hands. They can’t use the traditional style of poetry to portray this war. So they find new forms. And there’s no accident that modernists, literary modernists, receive a huge boost from World War One because forms, the traditional forms, break down. They need to find new ways to think through things.

I think this is a deliberately post-modernist novel by which I mean it is one that is highly self-referential. It talks about its own process a lot and those of you who read it kind of noticed that. And it also kind of critically undermines our sense of the real. So once we are in that store, we think we are in that story’s world, but that’s what we don’t get. In the story right after it saying that last story was all wrong. At the end, we are very unsure what to believe or what not to believe.

But I think there’s an interesting little section here – the section on “Good Form” – this is not really a short story at all, though it is in this collection. It’s a two page kind of essay on how to write about Vietnam. And what he says here:

“It’s time to be blunt. I’m 43 years old, true, and I’m a writer now, and a long time ago I walked Quan Linguy province as a foot soldier.”

And all that is not just true in this selection, it’s literally true of Tim O’Brien.

“Almost everything else is invented. But it’s not a game, it’s a form. Right here, right now, (inaudible) myself, I’m thinking of all I want to tell you about why the book is written the way it is”

A very weird thing to tell you in the middle of a book.

“For instance, I want to tell you this: Twenty years ago I watched a man die on a trail near the village of My Key. I did not kill him.”

Now this contradicts the story we just read in which he killed him, called “The Man I Killed” … so he didn’t kill him, he’s denying it.

“But I was present and my presence was guilt enough. I remember his face, which was not a pretty face … but listen, even that story [“The Man I Killed”] is made up. I want you to feel what I felt. I want you to know why story-truth is truer sometimes than happening-truth. Here’s the happening-truth: I was once a soldier. There were many bodies, bodies with real faces, but I was young then and I was afraid to look. And now twenty years later, I’m left with faceless responsibility and faceless grief, which of course would make a very bad story. Here is the story truth: He was a slim, dead almost dainty young man of about twenty. He lay in the center of a red clay village near the village of My Key,etc. What stories can do, I guess, is make things present. Daddy tell the truth, Kathleen would say [O’Brien’s 9-year old daughter] Did you every kill anybody? And I can honestly say ‘of course not’ or I can say honestly ‘yes.’”

What do we do with that? He’s undermining our basic structures of belief here. He’s saying there is no good way to interpret this war. There is no good way to simply represent it. And that notion of his that there’s a story-truth and a happening-truth, by the way, sounds almost exactly like what Oliver Stone says about Platoon, that no, it’s not real, but it’s as if it’s real. This sense that you have to create fiction to tell truth … it’s kind of central to his project here. Though what makes it very unusual is the sense in which he is constantly undermining that very story he tells. I think there are a couple of really classic instances here; probably the best of them is “The Man I Killed” talks about this man … from the story that we have just heard, he is killed. And then “Ambush” immediately afterwards, the first meeting we have with his daughter, Kathleen:

“When she was nine, my daughter Kathleen, asked if I had ever killed anyone. She knew about the war. She knew I’d been a soldier. ‘You keep writing these war stories,’ she said. ‘So I guess you must have killed somebody.’”

And then of course over the course of this it turns out that he hasn’t. And then we later get the story of he and Kathleen going back to Vietnam to visit one of the sites. Or alternatively, in that pairing, we get “Speaking of Courage” … that longish story that focuses on Norman Bawker’s story and the death of Kiowa. And by the way, the language here, he is very insistent that we have to keep this language. That this is the language of the war. It’s not incident to the way that the story is told. That Kiowa dies in a field of shit. It has to be shit. It can’t be some other polite word. But we get that, but then immediately after that we get this story, if it’s a story, called “Notes” in which he says: “Well, okay, this is based on Norman Bawker. He sent these letters to me. He killed himself shortly thereafter.” And even “Notes” undermines itself. So “Notes” tells Norma Bawker’s story. “He couldn’t tell it. Now I’m telling it for him.”

But then look at the very last paragraph of that story: “Now a decade after his death, I’m hoping that “Speaking of Courage” makes good on Norman Bawker’s silence. I hope it’s a better story.” But then, right at the bottom of that paragraph: “Even here it is not easy. In the interests of truth, however, I want to make it clear that Norman Bawker was in no way responsible for what happened to Kiowa, [which both the story before and “Notes” seem to say he was] … Norman did not experience a failure of nerve that night. He did not freeze up or lose the Silver Star for Valor. That part of the story is my own.” So he’s confessing that he’s the person who didn’t reach in a grab Kiowa out of the field of shit.

So we get this constant sort of undermining of our sense of reality. And I think as in Going After Cacciato, undermining our sense of reality is, O’Brien is convinced, the only way to come to terms with Vietnam. That our sense of reality doesn’t fit Vietnam. And part of that is about the very specific veterans’ experience of this kind of surreal war. We get a lot of that in other fiction and the films about Vietnam. But part of it is also about the gap … the gap between what people there experienced and what they can tell anybody else. The gap between those who’ve served and those who didn’t, which is a constant kind of tension in these stories. And it’s certainly there in this Norman Bawker case. You’ll remember Norman Bawker ends up circling that lake over and over again, trying to think how to tell his story and can never tell it to anybody. He imagines telling it to someone and what we really have is his imaging telling it rather than his telling it. This unrepresentable character where you can’t tell it to the people here is one of the themes present here.

In Vietnam in particular that was a big factor … the no parade sort of reentry issue with Vietnam. But I also think you can see this over and over and over again in other war experiences. World War One … all the classic fiction of World War One talks about it. All Quiet on the Western Front where Paul goes home, in three chapters, and he can’t talk to anybody. They can’t make sense of him, and he can’t make sense of them. Vera Brittain, who wasn’t at the front but was a woman working in the hospitals, can’t deal with it. It’s that interesting tension about representability. I think what O’Brien was up to here, and then I’ll shut up and let you guys talk, what O’Brien is up to here is trying to come up with a way to talk about the very unrepresentability by constantly questioning his own forms. By throwing out stories and then throwing out new stories that undermine the stories or throwing out little comments that undermine the stories and talking about all that explicitly. So even within the stories you’ll see several times someone will start telling a story and someone will else say “Oh come on. Tell it right.” That’s an interesting tension that goes through all this stuff.

So, what did you guys think?

One thought on “Big Read Discussion #1 ~ Opening Remarks by Professor Prasch”

Comments are closed.