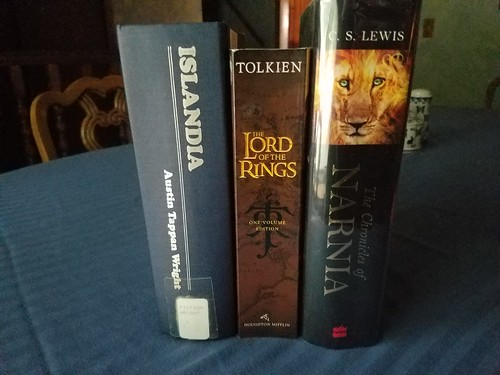

I’m in the final phase of my Hugo finalist reading, concentrating on the Best Novel category. In the right-hand panel of my blog, you’ll find my “Currently Reading” widget which is just the RSS feed for my GoodReads status updates. Three of the four books I’m currently actively reading are finalists. I’m listening, or attempting to listen despite major shortcomings of the Axis 360 app, to Ann Leckie’s Provenance. When I get too frustrated with listening, I switch to the ebook edition. Last night and this morning, I’ve been powering through the middle of Raven Stratagem. Earlier this week and most of last weekend, I immersed myself in the 1943 Best Novel finalist Islandia by Austin Tappan Wright.

I wish there existed a well researched biography of Mr. Wright, aside from the few paragraphs found in his Wikipedia entry. His immediate family alone would make for an interesting read as well: “He was the son of classical scholar John Henry Wright and novelist Mary Tappan Wright, the brother of geographer John Kirtland Wright, and the grandfather of editor Tappan Wright King.” (Wikipedia). His father, John Henry, “joined Johns Hopkins as a professor of classical philology.” Yes, a bell just went off in my brain (and yours most likely, if you happen to be a reader of a contemporary of Wright’s time: J.R.R. Tolkien). Granted Tolkien was a philologist who “specialized in English philology at university and in 1915 graduated with Old Norse as his special subject” where Austin’s father focused on the classical languages. Here are two brief explanations from Wikipedia’s Philology article:

I wish there existed a well researched biography of Mr. Wright, aside from the few paragraphs found in his Wikipedia entry. His immediate family alone would make for an interesting read as well: “He was the son of classical scholar John Henry Wright and novelist Mary Tappan Wright, the brother of geographer John Kirtland Wright, and the grandfather of editor Tappan Wright King.” (Wikipedia). His father, John Henry, “joined Johns Hopkins as a professor of classical philology.” Yes, a bell just went off in my brain (and yours most likely, if you happen to be a reader of a contemporary of Wright’s time: J.R.R. Tolkien). Granted Tolkien was a philologist who “specialized in English philology at university and in 1915 graduated with Old Norse as his special subject” where Austin’s father focused on the classical languages. Here are two brief explanations from Wikipedia’s Philology article:

Philology is the study of language in oral and written historical sources; it is a combination of literary criticism, history, and linguistics.[1] Philology is more commonly defined as the study of literary texts as well as oral and written records, the establishment of their authenticity and their original form, and the determination of their meaning. A person who pursues this kind of study is known as a philologist.

…

Classical philology studies classical languages. Classical philology principally originated from the Library of Pergamum and the Library of Alexandria[4] around the fourth century BCE, continued by Greeks and Romans throughout the Roman/Byzantine Empire. It was preserved and promoted during the Islamic Golden Age, and eventually resumed by European scholars of the Renaissance, where it was soon joined by philologies of other non-Asian (European) (Germanic, Celtic), Eurasian (Slavistics, etc.) and Asian (Arabic, Persian, Sanskrit, Chinese, etc.) languages. Indo-European studies involves the comparative philology of all Indo-European languages.

Perhaps by now I’ve completely lost you as I fell down this rabbit hole. But please, bear with me a moment longer while I attempt to connect some disparate dots for you.

When I first checked out Islandia from my local library in early April, I sighed and groaned just a bit. I was expecting that most 1943 Retro Hugo Best Novel finalists would be of the pulp-fiction length, easily read on a Sunday afternoon. At over a thousand pages, it is almost three times as long as the next longest finalist and more than six times as long as Heinlein’s.

- 352 pages – The Uninvited

- 254 pages – Second Stage Lensmen

- 184 pages – Donovan’s Brain

- 181 pages – Darkness and the Light

- 158 pages – Beyond This Horizon

On the other hand, I never shirk from tomes. In fact, I actively seek them out. When I was younger and poorer, I wanted the most reading bang for my buck so I gravitated to epic fantasy. Millions of words and hundreds of thousands of pages later, I find myself once again completely immersed in an alternate reality credibly built from the imagination of Austin Tappan Wright.

Mr. Wright’s worldbuilding is stunning and includes language, a clear indication of the influence of his father, yet I can feel his mother’s literary impact as well. His depiction of women in Islandian society is refreshing and I clearly see why Sherri S. Tepper recommends and frequently rereads Islandia. My only minor complaint would be the romantic fumblings of the protagonist, John Lang, but given his age (a recent graduate of Harvard so probably mid-twenties), the time period (supposedly 1907) and the fact that he’s a guy, I’ll not let this deter me from enjoying the rest of his adventures in Islandia.

Earlier this week, I became obsessed with finding an edition of a pamphlet that was published concurrently with the novel in 1942. Sadly, it is a rare book and in several special collections in various libraries around the country, but none closer than two hundred miles. Ironically, Mr. Wright’s entire manuscript, all twenty-three hundred pages, were scanned and are available online thanks to the Houghton Library at Harvard, including a detailed map:

The story behind the posthumous publication of Mr. Wright’s life work is itself fascinating:

Few people outside Wright’s own family knew he had long been working on an extensive Utopian fantasy about an imaginary country he called Islandia, with an elaborately worked-out history, culture and geography, comparable in scope to J. R. R. Tolkien’s life-long writings of Middle-earth. In his papers he left a 2300-page manuscript of a novel exploring the country, with appendices including a glossary of the Islandian language, population tables, a historic peerage, and a gazetteer and history of each of its provinces. Another book-length manuscript purported to be a general history of the country.

After Wright’s death his widow typed and edited the manuscript for publication, and following her own death in 1937 their daughter Sylvia further edited and cut the text; the novel Islandia, shorn of Wright’s appendices, was finally published in 1942, along with a promotional pamphlet by Basil Davenport, An introduction to Islandia; its history, customs, laws, language, and geography, based on the original supplementary material.

Since I was able to locate several copies of Davenport’s An Introduction to Islandia via Worldcat, I took a shot at requesting a copy via interlibrary loan. But, due to the fact that this pamphlet is only in special collections and not generally allowed to be checked out, I will have to make arrangements to view it the next time I’m in the St. Louis area.

By this point, if you’re still reading this, you’re probably wondering when I’m going to get around to connecting dots. No, I haven’t forgotten, but yes, I am easily distracted. The dots I’m trying to connect, albeit ineptly and hinted at above, are between Wright and Tolkien. Wright’s utopian masterpiece sprung up from the fertile yet quickly vanishing soil of the post Victorian pre-WWI era, while Tolkien’s subcreation bears influences from his Great War experiences, his love of languages and his Catholicism.

Both Islandia and Middle-Earth exemplify exceptional worldbuilding of which I can never get enough. Hence, my love for epic sagas. I pity the other 1943 Retro Hugo Best Novel Finalists because Islandia is going to be a very hard act to follow.

Sources:

- Wikipedia contributors. (2018, February 9). Austin Tappan Wright. In Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Retrieved 12:22, June 2, 2018, from https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Austin_Tappan_Wright&oldid=824746799

- Wikipedia contributors. (2017, August 13). John Henry Wright. In Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Retrieved 12:28, June 2, 2018, from https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=John_Henry_Wright&oldid=795299631

- Wikipedia contributors. (2018, May 29). J. R. R. Tolkien. In Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Retrieved 12:32, June 2, 2018, from https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=J._R._R._Tolkien&oldid=843500798

- Wikipedia contributors. (2018, May 30). Philology. In Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Retrieved 12:35, June 2, 2018, from https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Philology&oldid=843658681

- Wright, A., Bacon, Leonard, Davis, Elmer Holmes, Perkins, Maxwell E., Wright, John Kirtland, & Farrar & Rinehart. (1901). Austin Tappan Wright Papers, 1901-1958. http://id.lib.harvard.edu/aleph/000602250/catalog

Reblogged this on As a Matter of Fancy and commented:

Worth looking into.

There is a rare passion and persistence in those who dedicate a large part of their lives to a single writing project. I’ve spent 18 years so far on getting through the first 1-1/4 of mine, but I did publish the first volume. Too bad Mr. Wright didn’t get that pleasure. It is a significant one.

What happens after that isn’t up to the writer.

Thanks for the story of the story.